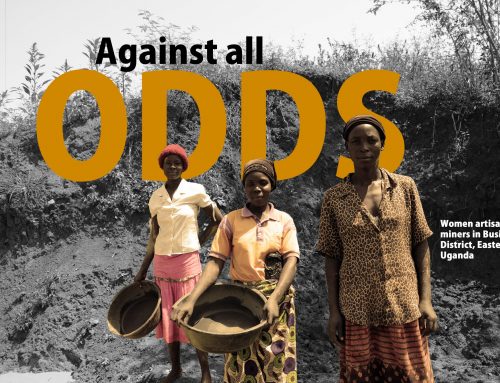

Julius contacted me via this blog back in January of this year. A Kenyan born activist, Julius had grown tired of the endless fundraising form filling you need to undertake when you work with an NGO. As a local Migori County man he had grown up surrounded by artisanal small-scale miners and was familiar with the lifestyles, environmental impact and social conditions that the many thousands of miners endured in order to to pay there daily way in the world. So I was delighted when Julius showed a considerable amount of interest in how Fairtrade Fairmined Gold could work in his locality. We talked throughout the year and planned. One of the biggest reasons why Julius approached the Fairtrade process, was because the local miners wanted ‘to be free of the economic slavery forced on them by the Asian traders in the region’.

Migori County (MICA) Artisanal Mining COOP was established to allow the local miners and traders to come together and to formalise their relationships in such a way as they could move forward to achieve Fairtrade status and begin exporting their production directly to the international market. Additionally by removing themselves from the economic controls of the bigger traders they would be able to increase their prices and begin lifting themselves out of the poverty that this form of gold trading creates.

Illustratively, the local gold business works through networks of local traders, linking with the artisan miners and then selling their production back to central processing hubs were the production is weighed, tested for purity and then smelted into simple ‘doray’ bars (unrefined gold bars) before it is moved to Nairobi and then sold to refiners in Dubai. This system is funded at the front end by money from the traders, who due to their financing, control and monopolise the entire region. They buy the gold at discounted rates as much as -28% as I discovered and then adjust for purity. Many miners complain of dodgy scales and purity testing. For example, I had one local processor boast about his cheap PC computer that could scan gold and give a 100% accurate reading on the purity. The genius of this system is it keeps everyone in debt. The local trader may make an average commission as little as KSH 80-100 per gram that he buys on behalf of the Asian buyers with their money. Everyone owes money to these monopoly traders and therefore you have an effective and very efficient form of economic slavery. Any deviation from the proscribed process meets with a swift response as we were to find out.

Over the course of the year, I and others had worked with MICA to see them formalise into a COOP, secure a direct export license and then create a traceable supply chain that would link transparently the miner to the end purchaser of their gold. This in an of itself is progressive as we had to work our way through the myriad of prejudice that exists towards small-scale miners from the refiners, shipping companies and potential financiers and business men, all whose lives are linked to risk mitigation and protecting their investments. Although understandable to a degree, it becomes untenable when in the name of ethics and justice people expect the poor to underwrite their risk with personal guarantees etc.

Anyway with MICA at one end and CRED Jewellery stepping up to the plate to act as the buyer, we booked the trip with a view to enabling the first direct export of gold from a small-scale mining coop from Kenya in the history of the country. The simple aim to enable the COOP to export it first shipment and thereby open up a supply route that would give the COOP access to the international market as well as lay the foundations for a vital part of their becoming a Fairtrade certified mining operation.

However, and this is where it came unstuck, the financial, social, cultural and indentured relationships that have governed this area for so long were not happy with the idea of the local miners being free to export directly, as this would be an erosion of the power they have in the region. Traders have all the power in these artisanal relationships and the COOP discovered that the wrong trader in the mix can kill a process by simply using the economic leverage they have to dictate price, pre-finance behaviour and loyalty. As we came to the day of the trade, it became increasingly obvious that the big traders had a plant in the COOP who simply killed the opportunity, withheld a part of the services needed and prevented the COOP from delivering. That same evening certain members of the COOP were visited by local bully boys and everyone got the message that this movement towards economic independence was not going to be tolerated by the invisible status-quo.

It is a strange thing knowing that you are so near, yet so far. I literally watched the gold disappear in front of my eyes. It was all there, yet the COOP could not bring it all together and deliver and of course this all happened on the same day as the money for the shipment arrived in the COOP account. Also I was now being advised to get out of the area for awhile as things were heating up and the COOP were not happy about the deteriorating security situation. So with driver and passport to hand I jumped into a car and drove to Mwanza to visit some friends there, while the COOP waited for the situation to calm down.

I learned a very valuable lesson on this trip. Traders have the potential to create problems in a way that anyone in the fair trade movement must never underestimate. The Gold mafia are a very real obstacle to change and we must have a strategy for dealing with them. And also that a quality relationship is often forged in adversity, as opposed to success. In many ways the COOP needed to fail on the first trade so that they could fully understand the scale of the mountain they want to climb and how much work they will have to put into their dream.

The COOP I am pleased to say as we parted company with them having transferred the money back to the UK, were very clear of their continued commitment to becoming a Fairtrade COOP. Are now much clearer as to what the obstacles are and also the relationships that prevented their first shipment. In truth we stress tested the system and in doing so all have a greater understanding of what not to do in the future.

Is there a future? Yes there is, and I hope to be able to update everyone on our progress early in the New Year as CRED and MICA seek to facilitate Kenya’s first export from a local COOP.

This is a fascinating story. I would like to share it on my Facebook page so how about a share button to share the post?

Hi Angela, The FB button is at the end of the article, just scroll down.

Thank you, Greg, for this amazing update!

Very interesting story.

Good afternoon Greg, so any progress is the COOP exporting Gold? There are alot of miners in Western who want to break out from the influence of the Asian Traders – but they don’t know how. Please let me know if there has been progress via email.

Hi William, the real challenge for the COOP is funding or an investment partner. We have proven they can export directly, we have created a technology solution that will remove mercury and improve gold retention. The MICA group have been told by Solidaridad Kenya that they are not going to be included into the British Comic Relief investment into FT Gold project, so MICA are now looking for partners again.